Chasing Portraits

Travel and Culture Guest Author Series: Elizabeth Rynecki tracks down her great-grandfather's art stolen in WWII Poland

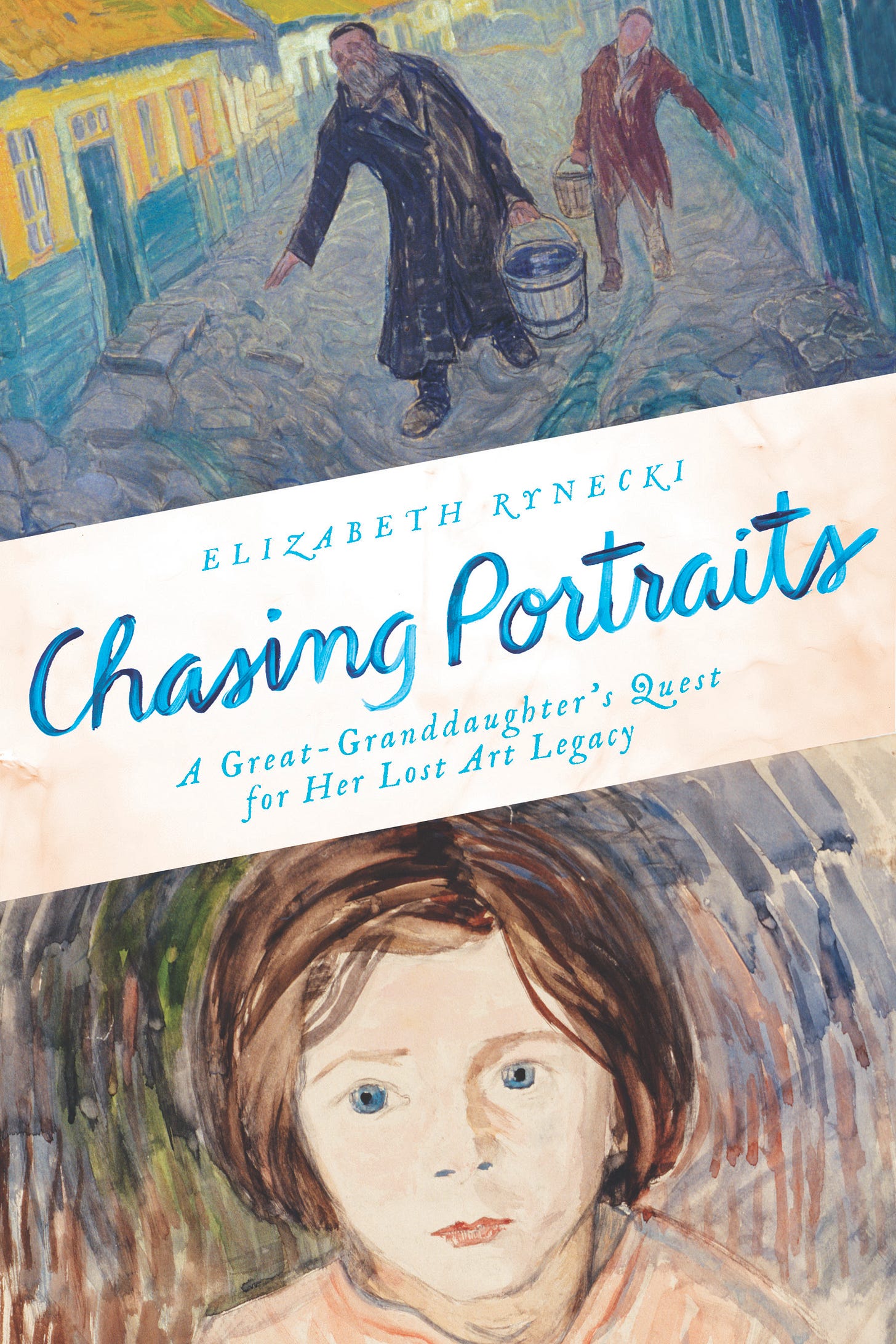

Art theft occurred on a massive scale during the Holocaust. Two generations later, the great-granddaughter of a Jewish artist set out on a journey to find his lost art. Her travels resulted in a book, Chasing Portraits: A Great Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy (NAL/Penguin Random House, 2016), which received a Kirkus Starred Review, and a documentary with the same name.

This is her story, and it is a privilege to interview Elizabeth Rynecki for our newsletter.

Moshe Rynecki: artist, Holocaust victim, and great-grandfather

In Poland, Moshe Rynecki’s corpus of paintings and sculptures of Jewish everday life included almost 800 pieces. Before he moved to the Warsaw ghetto, Moshe entrusted his life’s work to friends he thought would keep it safe. But Moshe was killed in a concentration camp. After the war, his paintings disappeared. His family recovered just a small percentage of the original body of work.

Two generations later, Elizabeth Rynecki, Moshe’s great-granddaughter, picked up the journals of her Grandpa George (Moshe’s son). The journals described the loss of Moshe’s art, and for the first time, Elizabeth realized there were a lot more paintings out there than the ones the family still had in its home in California. For more than a decade, Elizabeth searched for the lost paintings. She’s been fortunate enough to discover many of them in places around the world: Canada, France, Israel, Poland, and the United States.

Her search led her to Poland.

Meet Elizabeth Rynecki

Elizabeth Rynecki has a BA in Rhetoric from Bates College and an MA in Rhetoric and Communication from UC Davis. She lives in Oakland, California with her husband, two sons, and three black cats.

About 15 years ago, she embarked in a worldwide trip to track down Moshe’s lost artwork. “These paintings are like family members to me,” she says. They were an emotional bridge to the past, of culture and family life lost in the Holocaust, and they made her feel connected to Moshe.

After writing Chasing Portraits, Elizabeth also produced a documentary. The YouTube link is above and you can watch the trailer above. The film is available for purchase online.

And her award-winning podcast, That Sinking Feeling: Adventures in ADHD and Ship Salvage is available everywhere you get podcasts.

Poland made the stories come alive

Travel & Culture: What role did your travels to Poland play in your research and writing?

Elizabeth Rynecki: I never wanted to go to Poland. It represented a time and a place in history that was so devastating to my family. Like many children of survivors, I felt haunted by it. But as I embarked on making my documentary film and writing my book, it became clear I couldn’t tell the history without going. My Dad and I have a conversation about exactly this in the opening moments of the docfilm. He asks me how I feel about, “going back to Poland.” And I tell him I don’t know how I can go “back,” given that I’ve never even been. My father has zero interest in returning to his place of birth. But when it became clear I had to go, he was incredibly supportive.

As for writing about Poland, it appears in both the present and the past in my book. The first portion of my book is about my family’s pre-war and wartime experiences in Poland. I relied on my Grandpa George memoir a lot to write those scenes and I used my trip to Poland - walking those same streets, seeing and touching the Ghetto walls, retracing his footsteps, riding trains — to write about them in a more compelling first-hand experience sort of way. There’s nothing quite like standing in a place and realizing your father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all once called that place home. The trip to Poland made the stories come alive.

T&C: What experiences did you enjoy there? How did it change your perspective or affect your writing?

ER: This might sound strange, but for a long time Poland was, at least for me, stuck in the 1930 and 40s. It was all the black and white images I’d seen in museums, books, and films. It was a war-torn country. There was nothing there. But of course, that’s ridiculous. Wars destroy countries and families and communities, but eventually they (usually) rebuild. And that’s what Poland did both after WWII and after the fall of communism. So what was incredible for me was to see in Poland in living color. It was helpful to meet the people who call Poland home. Many of those people were kind in talking with me about the scenes in my great-grandfather’s paintings. Those chats helped to make his work livelier for me. For example, a park bench suddenly became a very specific park I could walk in and observe families enjoying a Saturday afternoon stroll. Or like the time I felt like I stepped into the farmer’s market scene my great-grandfather painted in Kazimierz Dolny. As I kid I didn’t understand that my great-grandfather painted real places and real people. Being able to sort of live in his paintings made everything more meaningful which made it possible for me to write more compelling prose (at least I hope that’s the case for readers!).

T&C: While you were there, did you try any new foods or local dishes? What do you remember about your dining experiences?

ER: The meal I remember the most, and one I wrote about in Chasing Portraits, was at a “Jewish” restaurant in Lublin called Madragora. I’d never quite felt so “othered” or so self-aware of my Jewishness. Maybe especially because I was in a place where so many Jews were murdered for being Jewish? But the chicken soup with dumplings were delicious and the massive plate of latkes both made me laugh and felt oddly comforting.

T&C: While you were there, did you have the ability to cook anything yourself? Or did you try to recreate the experience by cooking something when you got home again?

ER: I did not cook while I was in Poland. I was too busy filming footage for the documentary, interviewing people, and keeping an online blog so that I could remember everything later for my book! But I did love eating out. My favorite memories are of eating Zupa Grzybowa (Polish mushroom soup) and sipping Polish vodka.

I sadly could never find the vodka I had in Warsaw here in the United States (and now I don’t even remember the brand!). And while I did buy a Polish cookbook with a recipe for mushroom soup, I’ve never made it. In part that’s because we don’t have the same mushrooms here and in part because it’s just fun to hold onto the memory of the soup which is probably so much better than any mushroom soup I might attempt to make at home.

T&C: What did you see or experience of the local culture while you were there? How was it new or different for you?

ER: I don’t think this is exactly what you’re asking me to write about, but it’s the thing I keep thinking about… My name is Elizabeth Rynecki. But in Polish the “i” changes to an “a” for a girl/woman so I’d be a RyneckA. So my name is …. Wrong? Plus, I’ve grown up saying Rynecki as Rhine-eck-e (I think that’s a decent transliteration…) but the proper Polish pronounciation is Rinetski…. Or in my case, Rinetska. All of which is to say: I felt both like I belonged, and didn’t. I was born in California, I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. I’m not Polish. But I am? And yet I’m the wrong kind of Polish because I’m the daughter and granddaughter of Holocaust survivors and I’m Jewish and I don’t speak Polish. And that inspired others to let me know that while my name connected me to Poland, it wasn’t quite right, and that made me stand out in some unusual way.

Which reminds me that I also want to write a bit about Jewish figurines. Those are the “Lucky Jew,” dolls which are both totally silly and completely offensive. These often small figurines (although sometimes they’re paintings or large carvings) are caricatures of a Jew holding a zloty - a penny - that supposedly brings good luck. The irony, of course, is that they’re more popular than actual Polish Jews ever were. And so it felt weird to be retracing the places where my family members were murdered for being Jewish, but then at the same time vendors were hawking Jewish figurines as lucky? The cognitive dissonance is sort of mind boggling.

T&C: What would you tell someone else who wanted to travel to Poland?

ER: A big part of my trip to Poland involved engaging in thanotourism - visiting locations associated with death, tragedy, and human suffering. The tourist stops on my trip had everything to do with this history and not a lot to do with joyful, mindless relaxing tourism. If your readers are interested in learning more about Polish Jewish history in Warsaw, I highly recommend a visit to Polin: Museum of the History of Polish Jews, the Jewish Historical Institute, and taking a walking tour to see fragments of the ghetto wall.

Although I did visit Krakow, I did not have time to visit the Schindler factory, Auschwitz, or the Wawel Castle, but I did visit the Galicia Museum and I highly recommend it. On a more lighthearted note, a visit to Krakow isn’t complete without going to Cloth Hall, a popular place to find amber jewelry and souvenirs.

The other major city I visited was Lublin, because that’s the town closest to Majdanek, the Nazi concentration camp where we believe my great-grandfather perished.

The thing to see in Lublin is Grodzka Gate - both the historical gate itself as well as the arts group that is there working hard to call attention to Polish-Jewish history.

History tourism to Poland is particularly popular among children (and grandchildren) of survivors (e.g. A Real Pain was a hugely popular film that has this storyline at its core). But I also want to say that it’s super important for visitors doing this kind of tourism to make sure that they spend a bit of time getting to know modern Poland too. To do that I recommend visiting farmers markets, boutiques, and coffee shops.

T&C: Is there anything else you’d like to add about the experience or why it was memorable for you?

ER: One of the biggest reasons I went to Poland was to see the 52 paintings by my great-grandfather that the Jewish Historical Institute has in its collection. I’d seen some of the paintings in books before I went, but never all of them. It was an incredible experience to see the paintings. I immediately recognized his style in all of the works that they had. And for several of the paintings I discovered that he had made a painting of the same scene but with some minor differences from another work that I already knew quite well.

If you enjoy art, you’ll understand what I mean when I say that there’s nothing quite like being with original art. You can see things in an original work that you can’t quite see in a reproduction, even a good one. And these were the works of my great-grandfather. I never knew my great-grandfather. Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943) perished in the Holocaust long before I was born.

But there’s a self-portrait at the Jewish Historical Institute, a particularly compelling one, and for a moment I felt like I could reach back through time and actually touch him, meet him, let him know that I was working hard to make sure his history is not forgotten. That’s a moment that’s in the film - and a moment that gave me goosebumps.

Where to find Chasing Portraits

You can find Chasing Portraits: A Great Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy in libraries all over the world. The book is officially out of print, but you can still order a copy directly from Elizabeth. Use her contact form to let her know you’d like to buy a copy (or more!). She’ll email you payment options once you send your initial request. $20/book. She can ship via media mail anywhere in the U.S.

Legal disclaimer: We disclaim all liability for the content of websites to which our site provides links.

Great images! I love the way seeing Poland in "living colour" changed your perception of the country, based on your prior experience as well as your family's connection to it.

What a wonderful interview!