Family History becomes Historical Fiction: A Reporter's Approach with Vince Gledhill

Travel and Culture Guest Author Series: Interview with former journalist turned historical novelist, Vince Gledhill of Northumberland, UK

Vince Gledhill grew up in the 1950s before most households, including his, had a television. Books and magazines sparked his imagination and writing was his chief entertainment throughout his school years. He became a journalist and wrote for a group of daily newspapers in Northeast England for 45 years. Vince has written two books. One is a ghosted memoir called Cissie which tells the life story of Cissie Charlton, whose sons Bobby and Jack were both part of England's World Cup winning team in 1966. The other book, Sammy, is a work of fiction inspired by a conversation with his grandfather. He lives with his wife, Hazel, in Northumberland.

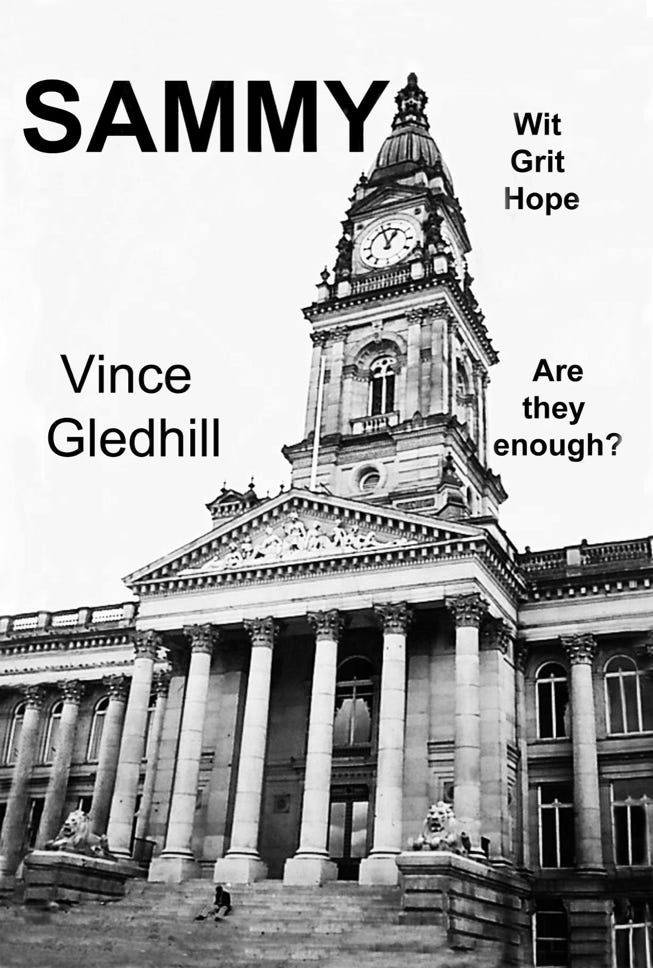

Sammy by Vince Gledhill

Sammy was 16 when his father abandoned him. It came unexpectedly. Both had been celebrating his sister's wedding in 1910, but his father left early. When Sammy got home, the door was locked, and a stranger answered his knocks. The man said Sammy's father had sold him the flat and everything in it. The boy suddenly found himself with only his clothes on his back and nowhere to go. His mother had died a couple years prior and his sister and her new husband didn't have the room to take him in. And Sammy never saw his father again.

The story of Sammy's survival and his trek across England to Northumberland to find work in the coal mines is based on a true story Vince Gledhill's grandfather told him about his own childhood. We are interviewing Vince today to talk about how he researched his novel Sammy.

Travel and Culture: How do you think your grandfather survived that ordeal? What kind of person was he, and how did the experience change him?

My grandfather survived that experience in much the same way that Sammy in the book survived it. By wits, ingenuity and human kindness. My grandfather met a number of people on his way from Lancashire to Northumberland who went out of their way to help him. He recalled one roadmender who let him share his hut for the night, the warmth of his brazier and his jam sandwich. In another place, a man who was as poor as granddad had no food, but shared the warmth of his borrowed bed for a cold night and on the last leg of his journey to Northumberland granddad was given a lift in a vegetable delivery cart.

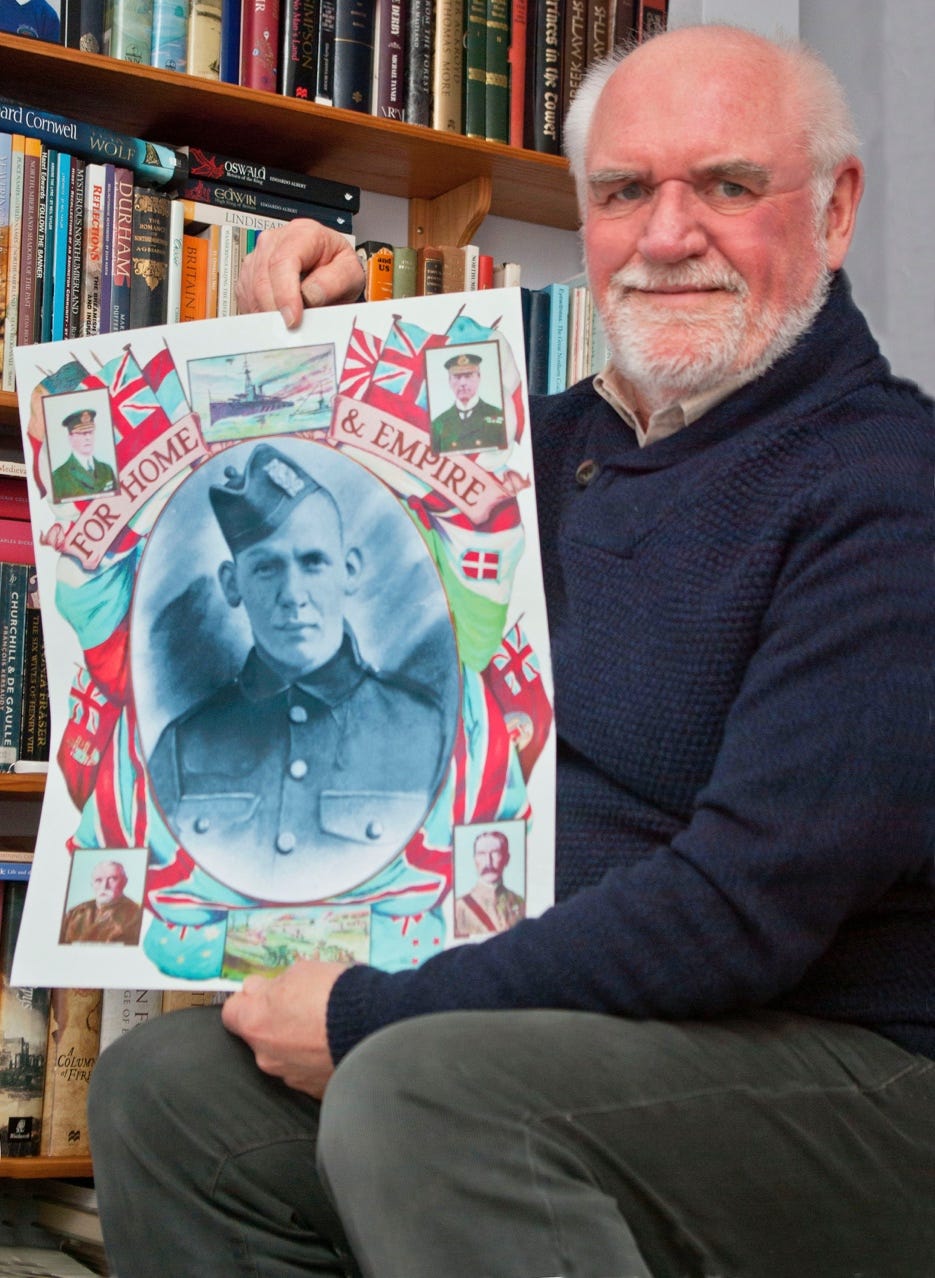

It is difficult to know whether or how it changed my granddad because I never knew the teenager he once was. But for the time that I did know him he was incredibly resilient. As a 20-year-old he joined the army and was one of the first sent to the Somme at the outbreak of World War One and one of the lucky few to survive that. He was blown up twice, once on the battlefield and once back in Britain when he was training new recruits to throw grenades and one of them misthrew a grenade which exploded at their feet, killing the new recruit and injuring my grandfather. After the war, he became a coal miner, went through the hardship of the 1926 miners’ strike. Later in life, when he was a widower, he became totally blind. His family did what they could for him, but he stubbornly insisted on staying in his own home, cooking and keeping house for himself. Eventually, after a bad fall, he very reluctantly agreed to move into my old room at my father’s house and lived there until he died at the age of 92.

T&C: What shocked us most about the story is that Sammy, as a 16-year-old, didn’t go to the authorities. If our parents had abandoned us at 16, we probably would have gone to a friend’s house and their parents would have called the police. Why do you think that didn’t happen?

In 1910, girls as young as 12 and boys of 14 could marry. Boys could also work underground in pits from the age of 12, so by the age of 16 it was taken for granted that they were well able to look after themselves. Hard times indeed.

In those days, people unable to look after themselves usually wound up being sent to a workhouse under Poor Laws that were not scrapped until 1929. Workhouses were generally places of cruel desperation to be avoided at all costs. Hence, when he was made homeless, my grandfather, like Sammy, sat on the steps of Bolton Town Hall and watched Reverend Popplewell, the preacher with a pram and a phonograph, before deciding to head North and hope for employment in one of the newly opened coal mines.

T&C: How did you do the research for the novel? What sources did you have from or about him, and how did you find them?

My research for the book began in 1968 and that brings me to an important point I want to make.

In 1968, I went to my grandfather’s house with a tape recorder. He was widowed and retired by then, but still had a sharp mind and a strong memory. I sat him down, switched on the recorder and said, “tell me about your life”. He was happy to do that and began by telling me how he had gone home from his sister’s wedding party to find a stranger at the door who refused to let him in. He talked for an hour and a half until the tape was full and told me about walking to Northumberland, getting married, joining the army, being blown up, working in the mines and his life until sitting down with me and the tape recorder.

When I decided to write a novel, I had all the memories in that recording to draw on. But, more importantly, now that I am older than he was then, I can still play that recording and be transported back more than half a century to sit in the living room of his colliery house and smell that coal fire with its built-in cast iron oven and see again every piece of black varnished furniture and hear the loudly ticking mantelpiece clock.

So, the important point I want to make to anyone reading this is that if you have grandparents who are alive, then sit down with them and a tape recorder and say, “tell me about your life.” If you are a grandparent, then sit down with your grandchild and give them the gift of your memories and the ability to return to that time and place, however many years go by.

Other research for the novel was done through the British Newspaper Archive, which has digitised and searchable copies of hundreds of national and local newspapers. I put that information to use through creative non-fiction.

T&C: You have been an excellent resource for us, in terms of sights to see in the region, like Corbridge and the Housesteads Roman Fort at Hadrian’s Wall. What else would you recommend, as the “must see” areas of Northumberland? Say, if a person only had one or two free days, what should they see?

If castles, bastles and fortified farmhouses are your thing, then Northumberland is the place to go. No other county in Britain has as many castles as Northumberland, because, as the county that sits on the edge of England and Scotland, it has witnessed hundreds of years of political conflict and cross border thievery.

The county’s 70 castles are in all in all stages of preservation and disintegration.

Some of them have become icons for the county, including Bamburgh, Alnwick, Lindisfarne, Dunstanburgh and Warkworth. Others are tucked away in villages and forests, including Aydon, Belsay, Berwick, Bothal, Chillingham, Etal, Ford, Mitford, Norham and Prudhoe.

Hadrian’s Wall is another Must See. It stretches for 73 miles from the Solway Firth in Cumbria across Northumberland to the unsurprisingly named town of Wallsend. In Wallsend is the area’s most excavated part of Hadrian’s Wall, Segedunum, which means Strong Fort.

National Trust properties in Northumberland that are worth a visit are Cragside, in Rothbury, Wallington, near Morpeth, and Delaval Hall, in Seaton Delaval. In different ways they capture the story of how Northumberland became what it is.

In Newcastle itself, the Great North Museum is worth a visit, as is the Discovery Museum, and the Laing Art Gallery, which is home to a number of Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

For people new to the city who have only one or two free days one of the best ways of getting your bearings, and a feeling for the place, is to hop on board one of the city tour buses which will introduce you to all the city’s main attractions.

T&C: You were a journalist for 45 years, working on a daily newspaper. I'm sure the experience gave you a unique perspective on the region. How would you describe the area and/or its people? What’s it like there?

I would describe Northumberland as cold and warm.

The prevailing wind most of the time is from the north and the east, where it passes over Scandinavia before crossing the North Sea, so temperatures above 25C are unusual. But the people are warm and welcoming and proud to have a reputation for hospitality.

In Victorian times, the Industrial Revolution began in the North East and demand for coal was suddenly huge, which gave rise to a Coal Rush in the parts of Northumberland that sat on huge reserves of the black gold. That meant that in the late 1800s and early 1900s, small villages suddenly grew into huge coal towns with the vast majority of the population found work in coal mines.

Work below ground is dangerous and demanding and very dependent on teams of people who can work in close collaboration. The result was the development of communities with strong bonds above and below ground, and I think that is probably at the root of the open friendliness that is the hallmark of Northumberland communities.

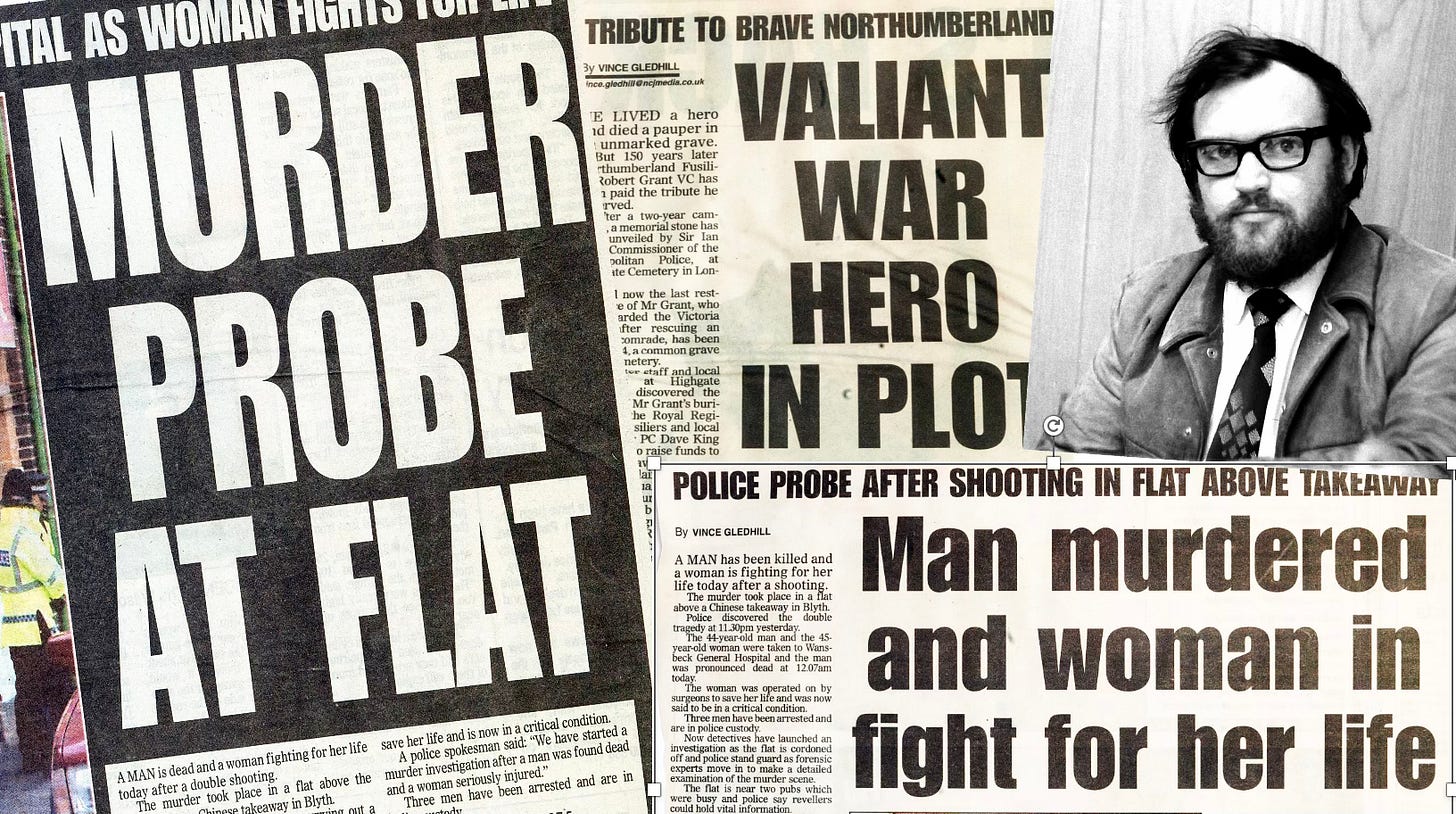

T&C: What was it like as a reporter in that period? What was your daily routine and your favourite “beat” or coverage area?

I began my career in journalism in 1964, working at the Newcastle headquarters of a group that published three newspapers, The Journal, the Evening Chronicle and the Sunday Sun. At that time, they were part of the Kemsley group of newspapers and the headquarters were in Kemsley House, a vast Victorian building dedicated entirely to the production of those newspapers, where every corner and corridor smelt of printer's ink. I loved that smell. Unfortunately for me, 12 months after I joined the company it became part of the Thomson publishing empire and a brand new headquarters was built next to the old Kemsley House and it was going to be many years before that printer’s ink smell permeated the new Thomson House.

It is easy to forget just how synonymous the region and its newspapers were in those days, but one figure tells the story. In the decade before I began working at Kemsley House the population of the Tyneside area, where it had its main sales, was 172,157 and the daily sale of the Evening Chronicle was 172,227. That is 100.04 percent, absolute saturation. So, when we knocked on a door on Tyneside, the newspaper we represented was already part of that household, which was sometimes an advantage and sometimes a disadvantage.

I always worked as a general reporter, not specialising in sport, or crime, or politics, but dipping in and out of all areas as the stories broke. Not knowing what each day would bring was a pleasure for me. I loved the spontaneity of the work, and the frenetic demand of a deadline driven job.

I spent the bulk of my working life with the Evening Chronicle in district offices around Northumberland and Durham, and that meant an early rise to each day. I would be at the office by 7 am to start making calls. That involved ringing police, fire, ambulance and coastguard stations around the area to find out about any incidents overnight and investigating further any of them that were interesting. Then it was time to read local and national newspapers for stories that we might have missed to see if there was any way we could find a new angle to the tale.

After that, it was time to call the news desk and tell the news editor what my plans were for the day and whether I had something from the calls or newspapers. The news editor might even have something to pass on to me.

The Evening Chronicle was printed later that day, so any news stories I had needed to be submitted by a deadline of 11am to make that day’s edition, which would appear on the streets of Newcastle from 1pm.

Some of my stories were not time-sensitive and those could be used in a future issue. They were called Overnights, because they could be held overnight for printing in the next day or two.

My work also included covering various courts in my area as well as meetings of local councils, inquests, and hard news stories, including murders and major crimes, as well as staying in touch with my contacts. All of that was in addition to digging through council reports for information that may have been buried at the back of a financial report that could provide an explosive tale.

T&C: Are there one or two stories you can recall that seem to reflect the area and/or the people? Tell us about it.

World Cup footballer Jack Charlton was a typical Northumbrian. In his younger days, he spent all of his free time outdoors, wandering country lanes, learning about wildlife, fishing and talking to whoever he met. He was proud of his accent and his heritage and when he was rich and famous and able to live wherever he chose; he set up home back in Northumberland and loved wandering the Northumberland countryside, fishing, talking and still learning about wildlife.

In his later years he brought his wife Pat back to Northumberland and their last home. Once a week Pat had her hair done in Ashington, in the town where Jack was born, and Jack came with her. While she was with her hairdresser, he walked along the promenade in neighbouring Newbiggin by the Sea and chatted to whoever stopped him to say hello. His walk along the prom took him to Newbiggin Golf Club where he had a coffee and a chat usually with an old friend who had been a classmate at an Ashington school 70 years earlier.

I think Jack’s tale embodies characteristics that Northumbrian’s take pride in, characteristics of working hard with what skills you possess, taking pride in your heritage and never forgetting the friends you make on the way.

T&C: When and why did you decide that you wanted to write books? How did that transition happen?

I had a different motivation for writing each of my books. I wrote Cissie when Cissie Charlton asked me if I would ghost her autobiography. Other journalists had asked if they could write her story, but they were sports reporters, and she knew that they would turn her tale into a story about her sons Bobby and Jack. She asked me to write it because she had known me since I was very young. I had been in the same class at school as Tommy Charlton, the youngest of her four sons, Tommy, and she knew I was far more interested in her story than football. I had also called at her home in Ashington many times over the years when I was a reporter based in the town and she knew the way I wrote and reported.

The novel Sammy came about because I wanted to find out whether I had the discipline to write a work of fiction. Plus, I had ended my full-time reporting career and that old need to write still burned in me.

T&C: Do you think of Sammy as creative nonfiction, or as historical fiction? Why?

I started out to write Sammy as a piece of historical fiction, but the approach I took to the research was a reporter’s approach. I found myself more comfortable digging out lost or hidden factual details and using those as the basis for events in the book. I brought a creative twist to those and enjoyed the freedom that gave me to play around with the facts.

For instance, as I had Sammy walk to a new location, I plotted it on a timeline so that I always knew which day he was in that location. From that, I was able to unearth the local paper for that place and discover what the weather was, what events were being reported, what people were talking about. Once I did that, I could walk alongside Sammy as he looked around this place and have the feel of it. From there, I was able to let Sammy interact with his environment and the people in it to bring the scene to life.

As an example, I was looking in one newspaper for a town where he had just arrived and saw a tiny advertisement for a cab company which bragged that it was the only one with two lady cab drivers, who drove motorised vehicles for themselves and a local undertaker.

That was the nonfiction part. The creative element was when I had Sammy meet these two women and have a conversation with them based on things that were happening in the town at the time and the women would be aware of.

T&C: What would you tell someone else who wanted to travel to Northumberland? What tips can you give us based on your experience?

The city’s Metro system is a convenient and comfortable way to get around Newcastle and surrounding areas, including Gateshead, North Tyneside, South Tyneside, and Sunderland. It also has services to Newcastle Airport and Newcastle Central Railway Station.

T&C: You’ve taken lots of cooking classes. What’s your favourite food to cook (and eat, of course!)

Having taken part in a number of medieval cookery courses, I am quite partial to the flavours of the past with spices, herbs and slow cooked meats. One favourite is Bourbelier de Sanglier, a dish where a joint of pork is cooked slowly, all the time basting with a mix of red wine, and spices which include grains of paradise, long pepper. clove, ginger and nutmeg.

My favourite medieval dessert is tardepolene, a baked tart which includes pears, ricotta cheese, sweet wine, almonds, nutmeg, cinnamon.

T&C: What are the best and worst experiences you’ve had when recreating recipes at home?

My best cooking experience is always when I have made a medieval banquet for family or friends and at the end of it, all I can see is empty plates.

My worse experience by far was when I was trying to make elderberry wine using a pressure cooker. After thinking that I had vented away all the pressure, I unscrewed the top lid to discover that there was still enough residual pressure to spray hot elderberry juice into every corner and crevice of the kitchen.

T&C: Yikes! That must have been quite the clean-up job. Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to use about your experiences, Vince.

Vince Gledhill is a historical novelist from Northumberland, UK. His books can be found at the following links:

Sammy: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09QJST6L1 (eBook) and https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/1090387083(paperback)

Cissie: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B014T48M66 (eBook) and https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/1095650823 (paperback)

Legal disclaimer: We disclaim all liability for the content of websites to which our site provides links.

I can only imagine the explosion of elderberry wine! Interesting interview.