One hundred eighty nine years ago today, the mayor of Bönnigheim – my German town – died. He was murdered.

One of the Bönnigheim Historical Society’s reenactments of the murder. The city uses this photo to advertise my crime scene tours about this case, which you can book via my website. I give public tours in English and German every year, but you can also book them privately. Image © Boris Lehner, with permission.

Bönnigheim, a small town in the southwest German state of Baden-Württemberg, is nestled among vineyards that plunge down from the Stromberg-Heuchelberg mountain range just north of the Black Forest. At the time of the murder, the grape harvest was in full swing. The city’s four wine presses were working late into the night. When Mayor Johann Heinrich Rieber left an inn around 9:45 pm on October 21, 1835 to make the short walk home, the fragrance of crushed grape most crept silently along the town’s streets and alleys.

Bönnigheim’s vineyards in October. Image: Ann Marie Ackermann.

But something else crept silently down the streets. Rieber didn’t notice a man with a rifle trailing him. When Rieber reached his front door, the man sprayed him in the back with shot pellets. The mayor lived only 32 hours, just long enough to tell an investigator he didn’t see who did it, before he expired in the early morning hours of October 23, 1835.

Bönnigheim’s Historical Society also produced a film fthat recreates the murder. It was part of a museum exhibition about the crime. It’s only four minutes long and has English subtitles. You can watch it here:

Short film Mord am Bürgermeister (Murder of the Mayor). With permission of the Historische Gesellschaft Bönnigheim. You can also book a city or museum tour with the chairman, Kurt Sartorius, whose contact information is on the site.

Who really invented forensic ballistics?

Up until 2015, France took credit for inventing forensic ballistics – the fine art of identifying a weapon on the basis of a bullet it fired. Investigators examine the striations, or scratches, left on a bullet by a gun’s rifling, and compare them to bullets fired in the crime lab from the suspect weapon.

Alexandre Lacassagne, a French pathologist, was considered the father of forensic ballistics. He used the technique to identify a murder weapon in 1888 and published about it a year later.

This memorandum in the investigative file for the Bönnigheim murder — now housed in the Baden-Württemberg state archives in Ludwigsburg — describes the first known use of forensic ballistics to eliminate a suspect weapon.

But in 2015, when I sat in the German archives to read the investigation file, I was shocked to read how the investigating magistrate, Eduard Hammer, had used the same technique to rule out a suspect weapon in 1835. The murderer had used a rifle to shoot shot pellets, and his rifle left striations on the pellets. This is the memo to the file I found. The investigator’s old, Gothic handwriting states:

Then several shots were fired from the suspect weapon, namely with buckshot and smaller shot [the same combination with which the mayor was shot]; from a sack of sawdust two feet long and 1 ½ feet wide, the fired shot pellets were collected. They did not have the deep striations we found on the buckshot and smaller shot from the body.

Eduard Hammer was able to rule out the suspect weapon based on this comparison. In that moment he became the true father of forensic ballistics. He never got the credit because the case was still open and he couldn’t publish anything about his new-found technique. But now Baden-Württemberg is interested in acknowledging his contributions to forensic science.

Striations from rifling on shot pellets. These are not from the 1835 murder, but from test shooting at the state police lab in Stuttgart. There the ballistics technician recreated the conditions of the Rieber murder. Image: Volker Schäfer, Landeskriminalamt (state police) Baden-Württtemberg, with permission.

Test shooting in Baden-Württemberg’s state crime lab. The ballistics technician used a 19th-century pistol with the same rifling the murderer used to recreate the conditions of the Rieber murder. Image: Ann Marie Ackermann.

Two award-winning books

My research on this crime led to book contracts in both the United States and Germany.

The Kent State University Press published Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee in 2017. It won the Bronze Independent Publisher Book Award for True Crime in 2018. (I’ll write about the Robert E. Lee connection in a future post.) You can read an excerpt below.

The press graciously gave me permission to post the second chapter of my book – the one about how the murder happened – in this post. You can read it below.

The German publishing house Silberburg Verlag published a translation in 2019, Tod eines Mörders. It is now out of print, but you can still obtain a copy through Bönnigheim’s historical society, Bönnigheim’s city hall, or the Vinothek. This book won a regional crime award from the German Publishers and Booksellers Association and an accompanying monetary award from Germany’s Ministry of the Interior in 2019.

Which genre do you prefer, true crime or murder mysteries? And which books did you particularly enjoy?

Hefezopf – German braided yeast bread: Germany’s platypus recipe

Hefezopf. Image by Ann Marie Ackermann

Hefezopf is a platypus among German baked goods. South Germany’s braided yeast pastry defies categorization. Is it bread? Or is it cake? Opinions differ, and a 2008 doctoral dissertation at the University of Tübingen even dedicated pages of research to the question!

That’s because the Hefezopf has qualities of both bread and cake. It has yeast and egg, and is braided, so it looks and feels like a challah for the Jewish Sabbath. The challah is considered bread, not cake.

But the Hefezopf is a tad sweeter and heavier (it has butter in it). You’ll find sugar crystals sprinkled on top, and there are often raisins in the dough. So a lot of Germans say that crosses the line, making the Hefezopf a light cake.

But do we really need to take a position to enjoy this recipe?

The Hefezopf’s long (and spooky) tradition

If you bite into a Hefezopf, you’ll be getting a mouthful of history. For centuries, it has been associated with funerals. Although you can enjoy a Hefezopf at any time (every bakery in southern Germany will offer it), a centuries-long tradition makes it THE traditional food to serve at a Leichenschmaus, or funeral repast, in southern Germany. It’s certainly what the residents of my German town ate following the 1835 funeral of their assassinated mayor in a record-breaking murder case.

The evidence for that comes from the grave, of all places.

Old archaeological digs of Alemannic graves found braids of female human hair in men’s graves. Historians suspected an ancient custom: The widow of the deceased cut off her braid and put it into the grave.

In later graves, the braids of human hair were replaced by loaves of braided yeast bread. It became clear that the braid, not the hair, was the important symbol in ancient funeral traditions. The grave loaves were eventually replaced by Hefezopf at the modern funeral repast.

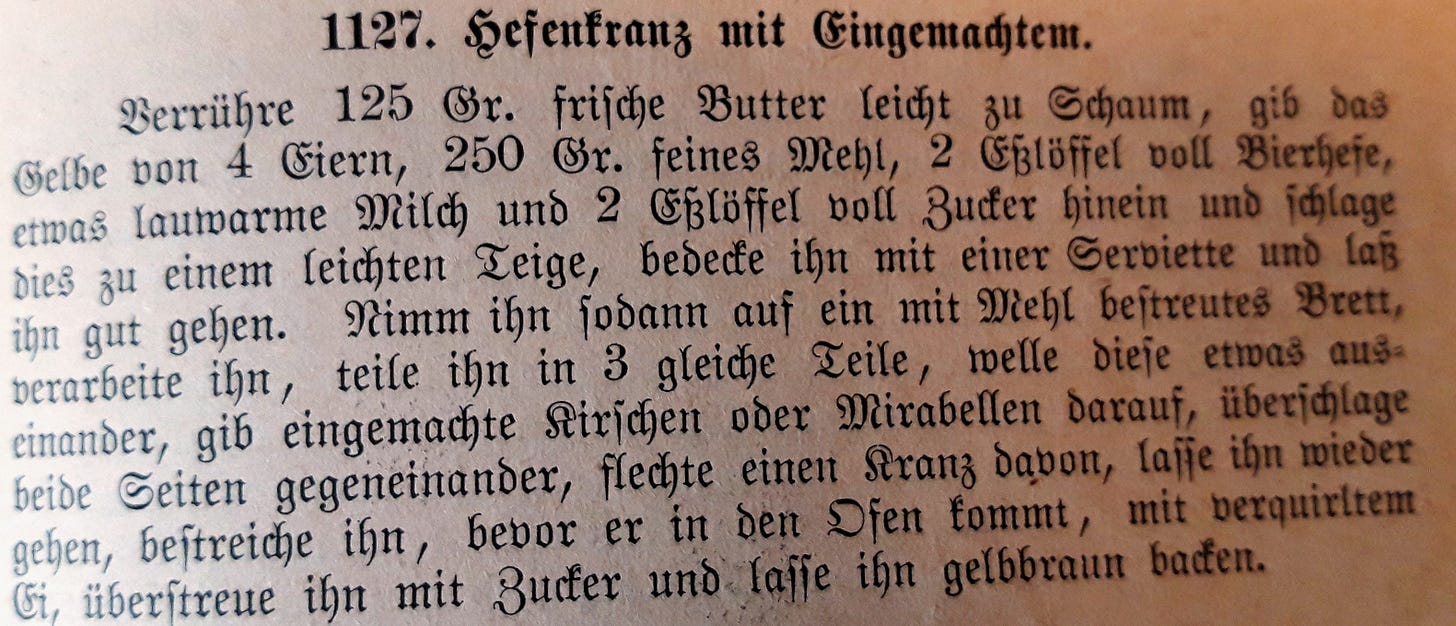

Old Hefezopf recipe

I found this old recipe in 1888 South German cookbook and can share it with you, because the copyright has expired. It’s for a Hefenkranz, or “yeast wreath,” which is the same as breaded yeast, except that you bring the edges of the braid together to form a wreath.

I used this recipe as a springboard for my baking.

Emma Rohr, Süddeutsches Kochbuch (Mannheim: Nemnich Verlag, 1888).

Yeast Wreath with Preserves

Beat 125g fresh butter until it becomes slightly foamy, then add 4 egg yolks, 250g fine flour, 2 T brewer’s yeast, some lukewarm milk and 2 T sugar, and mix the ingredients to a light dough, cover it with a napkin and let it rise. Then put it onto a board covered with flour, knead it, and divide it into 3 equal parts, roll them out, spread cherry or mirabelle preserves on top, braid a wreath and bring both sides together, let it rise again, brush beaten egg and sprinkle sugar on top before putting it into the oven, and let it bake until it’s golden brown.

Let’s make a few adjustments

A couple notes about this recipe, in case you try it:

The preserves aren’t traditional (I left them out), but sound like a delicious variation. I added raisins to my dough, which is more traditional today.

Did you notice that the author didn’t give any oven temperatures? That’s because in 1888, people baked with wood-fired ovens. Housewives judged the right temperature by the color of the oven’s stone walls. I baked mine at 180°C (about 350° F).

The author specifies “fine flour,” a term you won’t find today. You should use flour with a high gluten content to make fluffy bread. In Germany, that would be a 450 flour. In the United States, look for flour with a high protein content (12-14%), or a variety used to make pizza dough.

Follow the instructions on your yeast package to add the right proportion to the dough. Too much yeast in your dough could make it go flat once you transfer it to the baking tray.

Knead your dough well. At a molecular level, kneading stretches the gluten molecules. The longer the strands are, the more air bubbles they hold. That makes for fluffier bread.

The sugar Germans use to sprinkle on their Hefezopf is Hagelzucker, or sugar crystals.

Here’s the German flour I used. Image: Ann Marie Ackermann

Let us know if you try the recipe!

Have you ever tried a German Hefezopf? Or any other breaded bread, like a challah? What was your impression?

Legal disclaimer: We disclaim all liability for the content of websites to which our newsletter provides links.

Excerpt from Ann Marie Ackermann, Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee (Kent State University Press, 2017)

Reproduced with permission. © Kent State University Press. All rights reserved. I have removed the footnotes to make the text more readable.

Chapter Two

Crime Scene Bönnigheim, 1835

When Mayor Johann Heinrich Rieber left the Waldhorn Inn in Bonnigheim on October 21, 1835, he didn’t notice a man cradling a rifle and stalking him in the shadows. If he had, he might have had one last chance to save his life.

But the mayor was probably too distracted by his own grief to pay attention to his surroundings. He had spent the afternoon at the funeral of the town butcher, and that was a poignant reminder of his own loss. The funeral of his best friend—a school chum and local politician who had helped him promote a new school—had been held exactly one year prior.

Ever since his friend’s sudden death in October 1834, Bonnigheim’s pastor had observed a change in the mayor—a new contemplative despondency. Rieber grieved at the butcher’s funeral today and the pastor noticed it. He later described Rieber’s mood as “especially solemn.”

Bonnigheim, a small town nestled among the vineyards of the Kingdom of Wurttemberg in what is now southwest Germany, survived primarily from wine production and the hospitality industry, profiting from the busy trade route that cut right through the city. It had elected Rieber mayor in 1823 when he was only twenty-nine years old. Initially touched by the town’s expression of trust, Rieber soon found his youth and inexperience a liability; townsfolk felt freer to insult and threaten a young mayor than an older, more experienced official. Roving bands of boisterous youth created several crises in his early administration, disturbing the peace at night and even interrupting church services. Rieber responded by stepping up enforcement and penalties. Gaining the town’s respect dominated his attention at the beginning of his life term, but now, at the age of forty-one, he had largely won that battle. A proactive approach to the youth by establishing the new boys’ school and promoting education had become his new priorities; he even invested 900 Gulden—half the value of his own apartment—of his own money in the school.

By the evening of October 21, 1835, the unmarried and childless mayor felt so exhausted he fell asleep during his dinner. The Waldhorn, or “Hunting Horn,” was run by his older half-brother Karl Friedrich and his wife Rike (“REEKeh,” short for Friederike). Rike served him in a side room. Germans in the nineteenth century ate warm suppers, like the Spätzle dumplings with lentils and sausage so typical for the region. At this time of the year, people also enjoyed drinking fizzing and lightly fermented new wine from the winepresses. Rike said Mayor Rieber had arrived between 7:00 and 7:30 p.m. He sat alone, ate some supper, and drank only half his pint of wine. He told her he was tired and then dozed for more than an hour in his armchair. Several townspeople—a shoemaker, a lathe worker, and two foresters—arrived and dined in the Waldhorn, but the mayor slept through their conversations. The other patrons left before Rieber did.

Mayor Rieber had a stocky physique, an average height, and wore glasses. He was most certainly wearing the fashionable funeral attire of the day: black trousers, vest, and jacket, a broad black cravat at his throat, and a wide turnover collar.

The two foresters in the Waldhorn, Ludwig Schwarzwalder and Eduard Vischer (pronounced “fisher”), enjoyed an evening to themselves. Their boss was out of town for the night. They had plenty to discuss. Hunting season had begun and the forestry department had recently started interviewing applicants for a position as a game warden. Around 9:30 p.m. the two foresters rose, pulled on their standard-issue dark green, black-collared forester coats over their yellow vests, and left.

Ludwig and Eduard took the same route home that the mayor would take. Their destination was 140 yards away, where the end of the unpaved main street opened onto the Palace Square. A baroque palace, Bonnigheim’s largest building, dominated the plaza. They not only worked in the palace, they also lived there. Once nobility—among them Germany’s first best-selling novelist, Sophie von La Roche—had resided in the palace, but now it housed the regional forestry department administration and provided living quarters for some of its employees.

Bönnighem’s palace with the St. George fountain in the foreground. Mayor Rieber walked past this fountain on the way home. Image: Ann Marie Ackermann.

Neither man noticed anything unusual on the way home. Once in the palace, they climbed the stairs to their rooms and got ready for bed. Ludwig went over to Eduard’s room to chat with him for a while.

It was around 9:45 p.m. that the guileless mayor rose from his armchair, pulled on his heavy blue greatcoat, lit his lantern, and headed home. As soon as he stepped out the door onto the street, he would have smelled the heavy grape fragrance that always drifted through the streets and alleys, like mists of burgundy and the palest gold, whenever the winepresses operated. Bonnigheim had four presses within its city gates, and by late October 1835, they were all busy crushing the day’s harvest of Silvaner, Elbling, and Trollinger. Wood creaked late into the night as men pushed the spindle handles of the massive beam presses, and the sticky, sweet nectar flowed into wooden collection buckets. It was a good year; the grape harvest in 1835 was larger than usual.

From the Waldhorn, next to the town hall, Mayor Rieber turned right onto the main street. The mayor lived next to the palace in the Kavaliersbau (cavalier building), which he shared with the town physician, Dr. Nellmann, who lived and practiced above Rieber’s apartment, and a forest ranger named Ernst Philipp Foettinger, who lived in a rear wing.

It was dark and quiet outside on Bonnigheim’s main thoroughfare. The soft, damp earth of the unpaved street muted the footfall of any other person. Rieber’s lantern provided his main source of light. Bonnigheim did not yet have gas-lit streetlamps and the moon was new that night. The only artificial illumination came from the scattered, muted light of indoor oil lamps filtering through curtains. A few narrow alleys on either side of the street yawned like cavernous throats. But they appeared empty.

Mayor Rieber saw no one on the way.

About halfway home, he heard something. The report of two shots split the night. They sounded like they came from the churchyard and lower gate to his left. Rieber later told an investigator it bothered him that someone was shooting in town. But he didn’t feel threatened and continued walking.

In actuality, Rieber had been in danger ever since he left the Waldhorn, but unsuspecting, he forged ahead. As he passed the St. George fountain and reached the Palace Square, the night sky opened above him. If there was anything that distracted the mayor on the way home, it was the heavens above him. Halley’s Comet had recently reached its nearest point to earth for this return, and not since 1378 had it sailed such a close course for observers in the Northern Hemisphere. The comet’s tail cast a length twelve times the diameter of the moon. Here in southern Germany, rain and fog had veiled Halley since the beginning of September. One newspaper bemoaned the comet’s modesty and its refusal to “flaunt its charms and instead [keep] them veiled in fog.”11 But today the weather had cleared, offering the first good chance in weeks to see anything, and the moon was new. If the mayor peered in any direction on his short walk home, it was likely up, not around.

A high iron fence separated the public Palace Square from the palace’s inner, private courtyard. To reach his home, Rieber had to pass through a fourteen-foot-wide, solid wooden gate between that fence and the “washhouse,” where a forester named Stolzle lived. This gate led to the courtyard of Rieber’s home. It was locked, but it had a small door, just large enough for a person to pass through, and that was usually kept open. The mayor passed through the door, turned right, and cut a diagonal path across the courtyard to his home. He was now only a few steps away from his front door in the Kavaliersbau.

Wooden gates with doors are common architectural features in Germany. Image: Ann Marie Ackermann.

At that moment, a man with a rifle slipped out of the shadows. He took a position near the corner of the washhouse, eased up his barrel, and took aim across the courtyard. If Mayor Rieber had looked back at that moment, the muzzle might have been the only thing visible in the darkness on the other side of the courtyard.

The man pulled the trigger.

This time, the crack of the rifle was much louder. Mayor Rieber whipped around to apprehend the shooter. But he couldn’t see anyone.

The mayor didn’t realize at first that he’d been shot. After a few steps, he was seized with pain, and only then did he realize he’d been the target. Someone had sprayed him in the back with shot pellets.

Rapidly losing strength from the loss of blood, the mayor first cried out for help. Dr. Nellmann, the town physician, lived above Rieber’s apartment, and there was a chance he was there and could hear him. Rieber hollered “Doctor, doctor!” and careened into the Kavaliersbau. He staggered up one flight of stairs before he collapsed on the landing.

As the echo of his shot resounded from the palace and Kavaliersbau, the man with the rifle darted around the washhouse into one of the dark alleys Mayor Rieber had passed on the way home. Then, heading north, he disappeared into a narrow passage between two houses. With those steps, the clock started ticking on nineteenth-century Wurttemberg’s coldest case ever solved, and its only murder case ever solved in the United States by a third person.